Educational Toy Safety Testing: What Actually Happens in the Lab and Why It Matters?

Educational Toy Safety Testing: What Actually Happens in the Lab and Why It Matters?

Behind every educational toy that sparks curiosity and fuels a child’s development lies a hidden, crucial journey—one through the rigorous world of safety testing laboratories. For manufacturers, this process is a complex compliance hurdle; for parents, it’s an invisible shield they trust. But what does this shield actually entail? Moving beyond vague labels like "ASTM Certified," this article pulls back the curtain on the exact physical, chemical, and mechanical "torture tests" a toy endures before it reaches the shelf, and explains why this meticulous science is the non-negotiable foundation of true educational value and brand trust.

Educational toys undergo a multi-phase lab gauntlet: mechanical abuse tests that simulate a child's roughest play, precise chemical analysis for invisible toxins, and age-appropriate hazard checks. This process isn't about stifling fun, but about engineering safety into every design choice, ensuring the toy’s only "lesson" is a positive one.

To understand the depth of this process, we must follow the toy's path through the lab. This journey can be broken down into three core testing pillars, followed by the critical business and ethical implications of the results. Let’s step inside.

Pillar 1: How Do Labs Simulate a Child's "Worst-Case Scenario" Play?

The first and often most dramatic phase of testing subjects toys to calculated destruction. Labs use specialized machines and calibrated forces to replicate—and exceed—the stresses a toy might encounter from a curious, energetic child.

Labs don't assume gentle play; they engineer for failure. Key tests include torque and tension pulls on small parts, impact drop tests, and the definitive small parts cylinder test to prevent choking hazards.

[A series of three concise, labeled diagrams or icons:

Torque & Tension: An icon of a clamp pulling a small ball from a toy figure.

Drop Test: An icon of a toy being dropped from a marked height onto a hard surface.

Small Parts Cylinder: A diagram of a small toy part fitting inside a standardized cylinder with a diameter of 31.7mm, marked "Choking Hazard Test."]

Torque and Tension Tests: Using calibrated tools, technicians apply a specified force (in Newtons) to any component a child might grasp, pull, or twist—like a doll's eye, a button, or a wheel. The component must not detach or, if it does, must not fit into the small parts cylinder.

Impact and Drop Tests: Toys are repeatedly dropped from heights based on the child's age (e.g., onto a hardwood floor surface). This checks for breakage that could create sharp points, sharp edges, or dangerous, small fragments.

The Small Parts Cylinder: This is the universal judge for choking hazards for toys intended for children under 3. Any part of the toy, or any part that becomes detached during testing, that fits completely into this 31.7mm diameter cylinder fails immediately. This is a binary, non-negotiable safety gate.

Pillar 2: What Invisible Threats Are Labs Searching For?

While physical tests address obvious dangers, chemical analysis hunts for hidden risks. Children explore with their mouths, and their developing bodies are more vulnerable to toxic substances. Labs work to ensure no harmful lessons are learned through ingestion or skin contact.

Using advanced spectrometry and chromatography, labs screen for and quantify restricted substances like heavy metals (lead, cadmium), phthalates in plastics, and the migration of elements into simulated saliva or sweat.

Heavy Metal Analysis: Toys, especially those with paints, coatings, or pigments, are tested for soluble heavy metals. A sample is dissolved in a solution that mimics stomach acid or saliva, and instruments like ICP-OES measure the concentration of elements like lead, cadmium, and mercury that could leach out.

Phthalate and BPA Testing: Plastic components are chemically extracted and analyzed using GC-MS to identify and quantify plasticizers restricted due to endocrine-disrupting potential.

Material Screening: X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) guns are often used for rapid, non-destructive screening of materials for elevated levels of elements like lead, providing an initial check before more precise, destructive testing.

Comprehensive Substance Lists: Beyond common concerns, labs test for substances on lists like California's Proposition 65 or the EU's REACH SVHC (Substances of Very High Concern), depending on the target market.

Pillar 3: How Are Age and Developmental Stages Factored Into Testing?

Safety is not one-size-fits-all. A toy suitable for an 8-year-old could be deadly for an 18-month-old. Testing protocols are intrinsically tied to the manufacturer's stated age grade, which must be scientifically justifiable.

The labeled age recommendation dictates the severity of testing. Toys for under-3s face the strictest abuse and choking hazard checks. Testing also evaluates play patterns and potential misuse foreseeable for that age group.

Age Grading Justification: Manufacturers must provide a rationale for their age label. Labs assess the toy's play value, complexity, and safety features against known child development milestones. An improperly inflated age grade (labeling a complex chemistry set as 4+) is a major compliance failure.

Abuse Tests Scale with Age: The forces applied in tension, torque, and impact tests are greater for toys labeled for older children, who are stronger.

Hazard Profile Shifts: For older children, the focus expands. Magnet safety becomes critical (ingested magnets can cause internal injuries). Electrical safety (for battery-operated or plug-in toys), thermal hazards, and more complex mechanical hazards (like pinch points in construction sets) are evaluated. The lab asks: "What is a child of this age and development likely to do with this toy, even if not intended by the designer?"

Beyond the Report: What Do Test Results Truly Mean for Your Business and Your Customer?

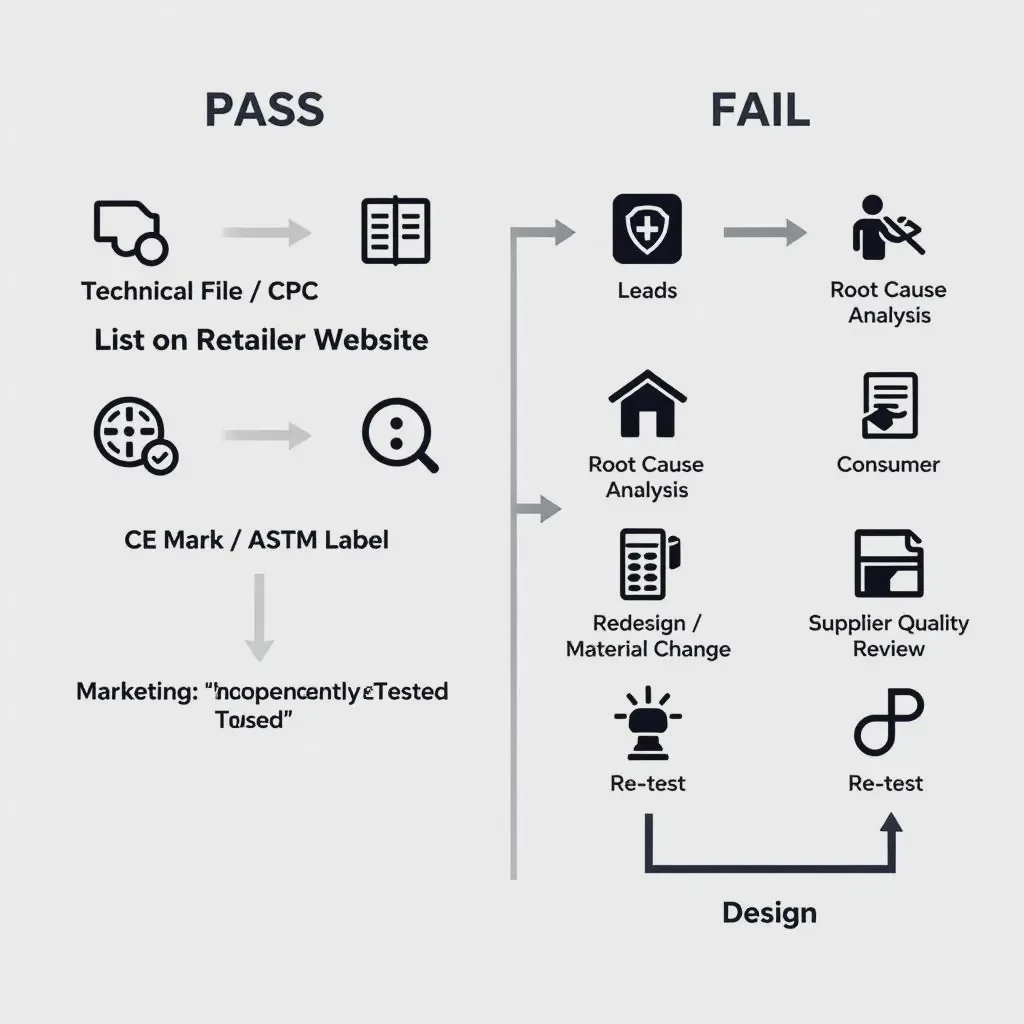

A passing test report is more than a compliance ticket; it's a strategic asset. Conversely, a failure is a costly but invaluable lesson. The implications ripple through product design, supply chain management, marketing, and consumer trust.

A pass is permission to build trust; a failure is a diagnostic for resilience. Smart manufacturers use testing not as a final gate, but as an integrated feedback loop for product development and risk management.

For the Business (The Manufacturer):

Pass: Enables the creation of legally required documentation (Children's Product Certificate in the US, Technical File in the EU). It satisfies retailer requirements and provides a powerful marketing claim ("Tested to ASTM F963").

Fail: While expensive, it pinpoints exact flaws. Was it a material issue from a specific supplier? A design weakness? This data is gold for corrective and preventive action (CAPA), preventing costly recalls and protecting brand reputation. It forces a stronger partnership with material suppliers and a more safety-centric design process.

For the Customer (The Parent/Educator):

The Test Report's Legacy: When they see a safety certification mark, it should represent this entire rigorous process. It signifies that an objective third party has validated that the toy's developmental benefits aren't undermined by hidden risks. This builds the essential trust that allows for worry-free, immersive play—the very state in which the best learning occurs.

Conclusion

The journey of an educational toy through a safety lab is a profound synthesis of science, regulation, and ethics. It translates the abstract goal of "child safety" into measurable, enforceable engineering and chemistry benchmarks. The mechanical tests ensure resilience, the chemical analyses ensure purity, and the age-graded assessments ensure appropriateness.

For businesses, embedding this testing mindset into the earliest stages of design is the ultimate strategy for sustainable success. For consumers, understanding this behind-the-scenes rigor empowers informed choices. Ultimately, comprehensive safety testing doesn't just protect children from harm; it protects the very promise of play. It ensures that the only takeaways from an educational toy are curiosity, skill, and joy—building a foundation of trust that allows learning to flourish.